Welcome to Artisan Spotlight, a column where we highlight Members’ favorite crafts and tradespeople, showing the work they bring to finished projects as well as the ways they view craftsmanship in a digitized world. This time, our subject is both a Member and a cherished resource.

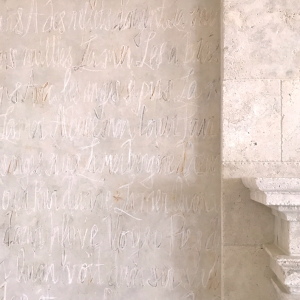

If terms like faux marbre and verre églomisé make your heart sing, then entering Simes Studios is like a trip to Willy Wonka’s factory. Here, under the direction of husband-and-wife duo Cindy and Jorge Simes, a bevy of artists toil in media ranging from glass to wood to watercolor, devising ever-new applications for art in interiors. On any given day, the studio may be devising a plan for a large-scale mural, testing new faux bois technique, or playing with various glass samples for a modern take on églomisé.

This conversation had been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us a little about how you two began with the work you do.

Cindy: We were both working in Buenos Aires, and I was doing my own art and some other jobs too, on the side. Some of my friends were architects and designers and they would ask if I could do a trompe l’oeil mural, or a faux marble. Around that time, a friend of mine came to the U.S. and brought back some books on decorative painting; I think I stayed up all night reading them. I was just poring over these thinking, this is a real job! I didn’t think I realized that before then.

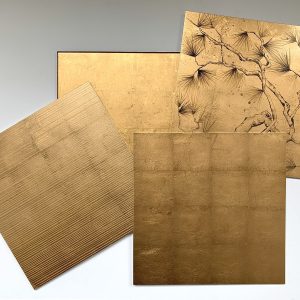

In an entryway by DLN Member Micheal Abrams, Simes Studios devised a shagreen lookalike in églomisé, which was installed in eight screens.

And how did you and Jorge meet?

Jorge: I was coming back and forth between Cordoba and Buenos Aires, and there was this couple; he was American, and she was from a very important family in Argentina. Every day, they would receive people in their house two or three times a day for these informal salons. It was just a constant flow of interesting people—and I was lucky to be a guest on and off.

Cindy: It was a Fellini-like dinner. I remember there was a Flamenco player and his girlfriend dressed in head-to-toe red and then an Ambassador…

This sounds like the makings of a fabulous play. So Jorge, what had you been up to at this point?

Jorge: My degree was in printmaking, which later on would be something that was very useful for what we do in the applied arts because a number of the techniques, including églomisé, are very much related to the mind of a printmaker, who has to do all his steps backwards. When you work on glass, you have to think backwards too.

And how did these foundations set you up for opening a studio?

Jorge: I realized around that time that the arts were something beyond whatever you do with galleries. And I was always attracted to the whole idea of applied art and the fact that you could actually be making a more reliable living by doing other things related to aesthetics, but not necessarily art galleries. One of them was designing fabrics, which I did for a couple of years. And then when Cindy and I met, we had all of these friends who were architects and interior designers. They really saw the scope of what we did together. And they would say, “I’m pretty sure you can do this,” or “I’m pretty sure you can do that” and they would just bring us jobs. So, so at one point, we realized that it was actually more reliable than art. It was something that you could be doing for for the long run, you know?

“There is basically a beautiful garden of images, waiting there to be discovered.”

Cindy: We came to Chicago in 1988, and we started working before we even had an apartment. There was this socialite here who was a friend of a friend of ours from Buenos Aires. And they said, oh, when you get to Chicago, give her a call. So I called her and she said, “come over for tea one day and bring your portfolios.” And that day, she was sick, and she said, “I’m leaving for Paris tomorrow for three months, but leave your portfolios with my doorman so I can see them.” I was afraid to leave them because I’m like, that’s all our work!

But I left it and when I picked it up the next day, she said, “this is the most beautiful work I’ve ever seen. She left a beautiful note and said, “go see these 10 top designers here in Chicago and tell them I sent you.” It was wonderful.

One of the things that’s so striking about your studio is the breadth of work that you do—from eglomisé to boiserie to mural; has that always been the case?

Jorge: I think that even though we care a lot about how things are made–execution is obviously super important—we place a lot of importance on research and development, too. We live in a privileged time in history where we can look back at pretty much anything and just reach out and it’s right there, whether it’s Byzantine or Brutalism. So we can craft ideas, and we can craft images and we can craft looks. And frankly, once you’ve crossed that threshold, there is no stopping. There is basically a beautiful garden of images, waiting there to be discovered. And you just keep working.

Cindy: The first couple years we were adapting to whatever people were asking for, and I think that was helping us. Someone would say, “can you do this painted floor?” I said, Yeah, I think so. Or a wall, or whatever; I think that’s kind of was setting the tone. We worked with some of those designers for 30 years, so I think that kind of investigation on each project into the materials and all the details kind of led us in the different directions that define us now.

So in the studio, do you have employees who are specialists in one or two crafts, or do people move around?

Cindy: Ideally, everybody’s well rounded. There are natural inclinations, of course, towards certain techniques or perhaps capabilities. So, it is important to look at the individual and see how to best use that talent. We definitely have people that are better at gilding or better at finishes or better at realism. So depending on the project that comes in is kind of the team that gets put together. But all of our artists go through a two to three year apprenticeship when they come in, so they get that training.

Everybody we hire has a degree in Fine Arts. A lot of them have a Master’s too. So what we find is even when they’re trained, we have to hire somebody that can draw up realism. So that’s the most important thing that they can see. Then, within their apprenticeship period, they pretty much try their hands at everything and we figure out where their strengths are.

“If the performer is tired, you can tell.”

That must make for a very collaborative office culture.

Cindy: I think one thing that differentiates us from a lot of studios, and that we’re really proud of, is that we try to hire everyone full time. We don’t let them work much overtime, and we do benefits, which is rare. We want to keep them doing their very best work. Many studios hire people freelance based on their projects.

Jorge: In all fairness, it took us time to get here. In our beginning, we did a lot of that. But what we realized is that it burns people out. And, you don’t get the quality you want.

Cindy: We don’t want them tired when they’re up on scaffolds all day. We want them doing their very best work every day and not working 12 hours a day to try to push out a project.

Jorge: The same is true with musicians, you know? If the performer is tired, you can tell.

Cindy: They get used to working together, too, which is so important. As an artist, you can have a huge ego, but as an applied artist, you have to be able to work with the designer and the client–even if they change their mind halfway through the process. We always look for people that are team players.

You mentioned that some of the art schools are no longer focusing on more traditional techniques–how does that impact your work and the industry at large?

Cindy: I think some of the bigger schools are doing artists a big disservice. I’ve seen many students come out of these schools, and it’s very far and few between that you can find one that actually has has been taught the basics of painting. There’s a lot of conceptual work, there’s a lot of installations, and I feel like they’re being sent out into the world with huge debt and loans because art schools are very expensive, and very few marketable skills. Most of these schools aren’t even giving any kind of business class.

They’re being taught that if they’re not the next biggest gallery artists, they are selling out if they’re doing applied arts. But why? I mean, famous artists over the centuries have done interiors, back to Michelangelo. Somehow in the last 100 years, it’s been turned around.

Jorge: I think it’s been misinterpreted. Applied arts are a good engine for exploring new media and making a living as an artist, but people have the illusion that there is only one way to define success. But that’s very much not true.